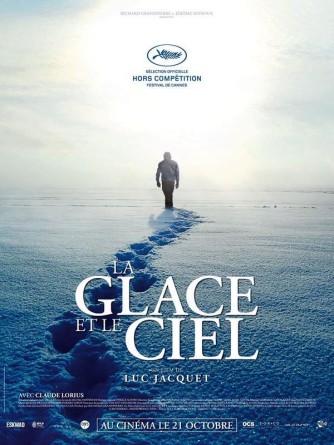

The decision to close the 68th Cannes Film Festival with Luc Jacquet’s poignant documentary, La glace et le ciel (“Ice and Sky”), sends a rather clear message: “let’s stop messing about and finally get down to business, eh?” In a press release straight from the proverbial horse’s mouth, the festival underlined that, “to program such a film is to send it into the future, and to encourage the success of the Climate Conference that will take place in Paris from November 30th to December 11th” of this year. No ambiguity, the festival is sending the most powerful message they can, so maybe we should all perk our ears up and have a listen.

Starting with the most superficial, “Ice and Sky” falls into line with most of the other films shown at Cannes this year in two important respects: it’s incredibly well done – beautiful to look at – and it drags just a little, tiny bit. Neither of these characteristics should come as a surprise, as I’m not sure there’s ever been an ugly, poorly made film shown at the festival, and we can hardly expect to be shown the same sort of superfluously compelling Hollywood narratives that tend to wither and fade in the memory. That’s why “Mad Max” and “Mockingjay” were playing across the street and not at the Palais des Festivals.

Ice and sky is not your typical climate change film. There are no time-lapse images of ice melting or of the stranded polar bears who seem to have questionably embodied the ecological movement for the past ten, fifteen years. Those films and this one differ in one important respect: they are made as essays, the ultimate goal of which is to convince. “Ice and Sky”, in a rather justified exasperation, has moved beyond “the debate.” As John Oliver so rightly put it in an episode of his show, Last Week Tonight, the subject of Climate Change might very well still seem like a real “debate”, because we often see two pundits on either side of a TV screen disputing “the facts.” This of course is a misrepresentation, since only about 3% of scientists who write about and study Climate Change still seem to have some inexplicably lingering doubts. “Ice and Sky” quietly and politely excuses itself from theatrics and instead focuses on the very personal. By recounting the life and career of Claude Lorius, the French scientist widely credited with discovering and proving the existence of Climate Change, we get to “understand the facts” ourselves. We get a small glimpse at the frustration and disappointment of a man who has spent almost his entire life (and at least 10 years in the Arctic) trying to convince us that our actions and prosperity over here have consequences over there.

If I have one modest quibble with the film, it would be that the destructive human activity that Monsieur Lorius has documented and studied isn’t on screen nearly enough. I assume that this was an intentional omission, as I’m sure M. Jacquet wanted to further underline the personal nature of Lorius’ story. I suppose the “bone” Jacquet obliged to throw those who share my critique was the manner in which he framed Lorius’ first voyage to the Arctic: at the dawn of “les Trente Glorieuses” – the economic prosperity that followed WWII – in the heat and excitement of industrialization, where the the planet’s resources seemed abundant and human potential, limitless. This would ultimately be the manifesto that would both drive our destruction of the planet, but also Claude Lorius’ personal commitment to documenting it.

Furthermore, the film is teeming with an abundance of fun anecdotes, especially for the scientifically inclined, particularly the account of Lorius’ eureka moment that yielded his method for Co2 and temperature analysis over hundreds of thousands of years (I’ll give you a hint: what does one chill their whiskey with in the Arctic?) Go see this film if you want a detailed and emotional account of a modern-day Ulysses with the noblest of causes. And who knows, maybe you’ll even start biking to work!

I think the admin of this web page is really working hard in support of his site, because here every information is quality based material.

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!